Global elimination of lymphatic filariasis accelerates its pace, backed by an array of local solutions driving success

172 million declared to no longer require treatment for lymphatic filariasis in 2024. In Nigeria, leaning into local solutions shows why.

By Ellie Leaning, Moses Aderogba, Kerry Gallo and Greg Porter

Photography by Omoregie Osakpolor

The number of people requiring treatment for lymphatic filariasis, a debilitating disease that causes irreversible swelling of the limbs, fell by a staggering 172 million from 2023 to 2024, the largest yearly change in more than a decade, according to recent figures released by the World Health Organization.

If everyone who no longer needed treatment in 2024 formed a nation, it would be the ninth largest country in the world. Since 2000, nearly 1 billion people worldwide have been freed from the need for annual treatment.

Lymphatic filariasis is a parasite spread by mosquitoes. Communities with the least access to resources are the most at risk. “Lymphatic filariasis is poverty-related, it thrives where there is poor sanitation, substandard housing, lack of access to potable water, poor personal and environmental hygiene,” explained Dr. Bosede, the NTD coordinator in the Federal District Territory, Nigeria.

Five years ago, Salamatu Sarkin Gaji, a 60-year-old woman from the Gaji community in Gwagwalada, Nigeria, first noticed the symptoms of lymphatic filariasis. She was likely infected by the mosquitoes that would bite while she worked on her farm. She experienced intense itching, and her leg began to swell. When the pain became severe, she had to stop whatever she was doing to rest. As a farmer, the loss in productivity was devastating.

The disease can be isolating, too. Studies show that people with lymphatic filariasis suffer from higher rates of depression and other mental problems due to the stigma from the disease and how it can ostracize people from their communities.

Since 2000, more than 10 billion donated treatments have been delivered for lymphatic filariasis, all of which were donated by Merck and GSK. The elimination strategy relies on regular mass treatments of a community to reduce the transmission, and these large-scale investments by pharmaceutical companies remain crucial to their success.

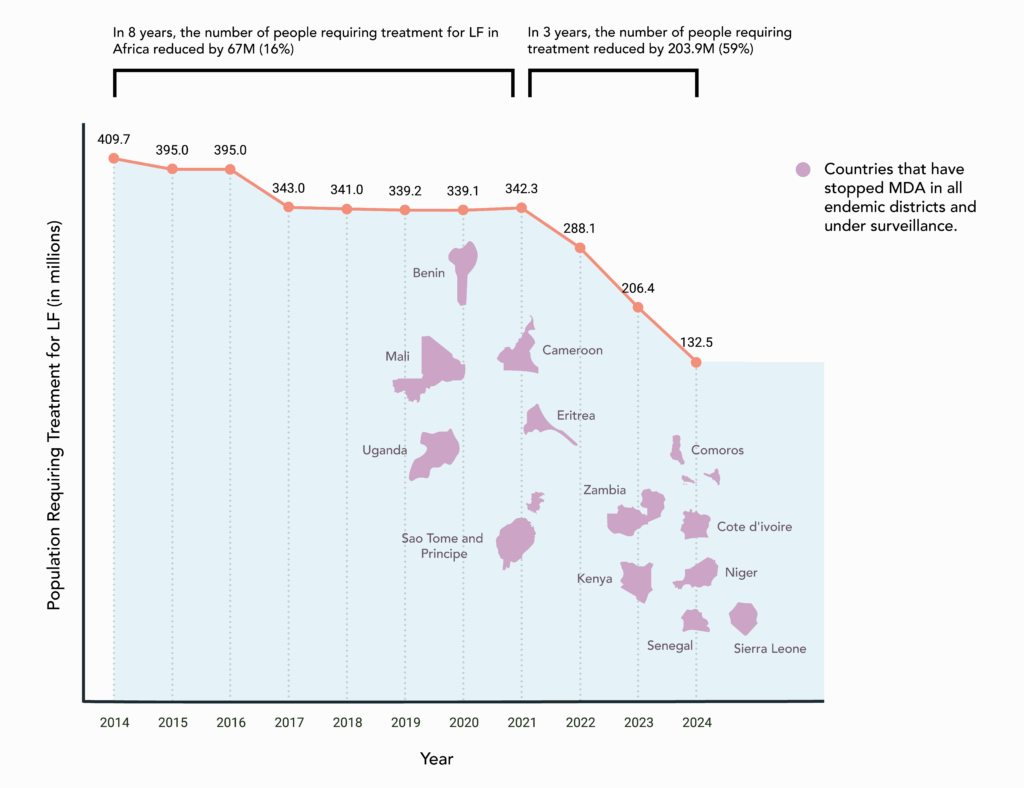

In the last three years, the WHO African region has seen the largest percent decline in people needing treatment of all the WHO regions. Only three countries have not been able to scale treatments to reach every endemic area in Africa. Five years ago, that number was seven. Today, 13 African countries have safely stopped population level treatment while they wait for disease surveillance data showing that transmission has lowered to below the threshold that the WHO deems sustainable, essentially stopping community level transmission.

One recent study analysed the reduction in lymphatic filariasis and noted that if current work continues, the burden of the parasitic disease should meet the WHO’s 2030 goal of global elimination.

This progress, however, is not a single, unified strategy. It is a compilation of a diverse array of sustained local programs. Nowhere is this more evident than in Nigeria. Ten years ago two thirds of the entire population in the country required treatment for lymphatic filariasis.

The scale of the problem is compounded by the vastness and complexity of the country. Nigeria is made up of 36 states and nearly 800 local government areas with different cultures, languages, and economic and political landscapes.

The number of people requiring treatment has reduced by 97 million people over the last five years and more than 22 million in the Federal Capital Territory, Ekiti, Ondo, and Bauchi states alone in the last year, reducing the country’s burden of disease by 72 percent, according to estimates calculated by the END Fund in April 2025.

Leaning on local communities to ensure a sustainable future

Nigeria’s Master Plan for Neglected Tropical Diseases emphasizes a localized approach, which empowers sub-national leaders to address their region’s unique challenges in efforts to eliminate lymphatic filariasis.

Dr. Bosede is clear-eyed about the reality. “We are really emphasizing community ownership, so it will be easier for the program to continue after the exit of our partners, because one day, the partners will go.”

While international support from organizations like the END Fund and its community of donors can fill gaps, convene diverse partners, and provide targeted technical support, it is critical to structure partnerships to build a sustainable program that is not dependent on external funds.

Engaging communities and local leaders is crucial to ensuring communities understand and accept health interventions. In the Federal Capital Territory, Dr. Bosede’s team and its partners engage respected community members and religious leaders, including the Traditional Rulers Council, to jointly plan program activities.

“We ask the traditional leaders to identify local community members to help us carry out mass administration of medicines,” explained Dr. Bosede. “The leaders look for people they trust. We train them and we entrust our medicines into their hands. The drug distributors move from house to house to administer the medicines. This is very important because if you send strangers, the community may not accept the drugs.” As a result of these efforts, more people are willing to be treated.

a heavy sensation in her leg and significant swelling. She relied on herbal remedies but saw no noticeable improvement. When she first sought medical help at a clinic, she was mistakenly diagnosed with cancer, which left her discouraged and resigned to her fate. However, she was later referred to a healthcare facility where trained professionals diagnosed her illness as a result of lymphatic filariasis and provided proper care. They cleaned her legs, educated her on how to self-manage her condition with massage and daily washing of her limbs. The clinic also supplied her with essential care materials such as a basin, towel, cotton wool, soap, and antibiotic ointment.

An ongoing approach, building a sustainable health system

The effects of lymphatic filariasis can linger even after the parasites have left a person’s body. They can continue to suffer from disabilities caused by the disease, and are at increased risk of bacterial infection.

“Individuals with existing lymphatic damage need lifelong care,” explained Achai Ijah, program officer with HANDS, a Nigerian organization supporting the neglected tropical disease program in the Federal Capital Territory. “They have limited access to proper hygiene materials, physical therapy, and psychological support.”

HANDS staff work with the Federal and State Ministries of Health and local hospitals to find people with swelling caused by lymphatic filariasis and connect them to local health centers.

Hajiya Amina has lived with the effects of lymphatic filariasis for more than 20 years. When she first sought medical help, she was mistakenly diagnosed with cancer. However, she was later referred to a health facility where trained professionals diagnosed her illness as a result of lymphatic filariasis and provided proper care. They cleaned her legs, and educated her on how to self-manage her condition with massage and daily washing.

Men suffering from hydrocele, a severe swelling of the scrotum caused by lymphatic filariasis, often require surgery to reverse the condition. Training more health workers to provide hydrocele surgeries at the local level has begun to lift the burden from patients who must otherwise travel far to receive care, and help the Federal and State Ministries of Health to reduce the backlog of hydrocele cases.

Since 2021, the END Fund and its community of donors have supported the Amen Health Foundation, CBM, the Federal Ministry of Health, HANDS, Helen Keller Intl, and MITOSATH to treat 5,200 people with lymphedema, and enabled 5,700 hydrocele surgeries across eight states in Nigeria.

The work supported by the END Fund in Nigeria is made possible by local commitments from organizations like NNPC Retail, NNPC Foundation, IHS Nigeria, and Nigeria First City Monument Bank.

Drug treatment is a powerful tool in controlling lymphatic filariasis, but elimination requires a broad range of interventions to address these factors. Dr. Bosede emphasized, “No matter how good the drug administration program is, without the involvement of partners in water, hygiene and sanitation improvements, it will not meet its full impact.”

People with lymphedema need daily access to clean water to wash their limbs and prevent infection. Furthermore, the mosquito that spreads lymphatic filariasis breeds in poorly maintained water bodies.

The successes against lymphatic filariasis proves that Nigeria’s strategy to eliminate neglected tropical diseases is working, but there is still much work to be done. Dr. Bosede highlighted the need for local funding from the national government, Nigerian philanthropies, and the private sector. She emphasized that securing local resources and the timely disbursement of funds to programs will be crucial to build the self-reliance Nigeria needs to sustain momentum.

Without this type of localized approach, global success would never be possible. As countries continue to reduce the need for mass treatments, it will free up resources to continue to build sustainable health infrastructure.

A recent impact survey found that transmission of lymphatic filariasis has been significantly reduced in Maimuna’s community. The cycle of disease was broken as a result of sustained drug treatment, and fewer people are at risk of becoming disabled by the disease.